10,000 hours. Learning styles. Left Brain/Right Brain. Lactic Acid. Sugar Highs. Three-cuing. Resilience. The category of Malcolm Gladwell-esque bs that people either uncritically parrot to sound smart, or worse, live by is long. Sadly, this is especially true for education and learning, which structurally enables poorly-vetted ‘research’ working its way into ‘best practices’ through “continuing education” requirements and the industry of workshops and funded curricula designed to flow from those CE units into classroom instruction.

That most of it has little to no grounding in truly reviewed, grounded, and replicable studies rarely matters since the raison d’etre is to fill in lines on evaluation forms and provide evidence that the people adopting them have means of showing that they are “highly effective educators” using “high impact practices” that develop “life-long learning” and a “growth mindset.” There might need to be a service-mark in there somewhere.

Here I am, here we are, surrounded by our century’s Gradgrinds—disguised under vaguely Freireian or hooksish verbiage—doing their level best to accommodate ‘educators’ and others to an educational ‘reality’ of their own perverted invention.

So. here I offer you a way of assembling circuits of thought and feeling based upon the reading, writing, practicing, and working devoted to repairing thermionic tube circuitry. What stops this from becoming an easily sloganable or workshoppable ‘product’ is the complex circumstances that make any attempt to derive analogies break down at the point where they might become facile analogies or slogans. Whether we talk about working on ourselves, or dare to work on others, even when routinized, the process is difficult, complicated, and the results unpredictable.

But. If we are willing to take some risks, willing to identify what it is we’re doing, and practice with the techniques, it is possible.

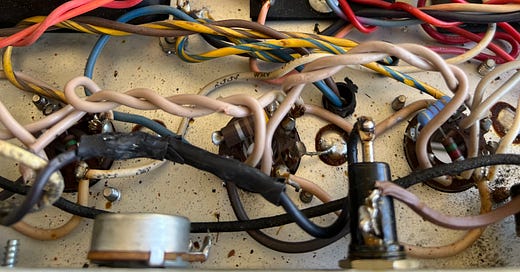

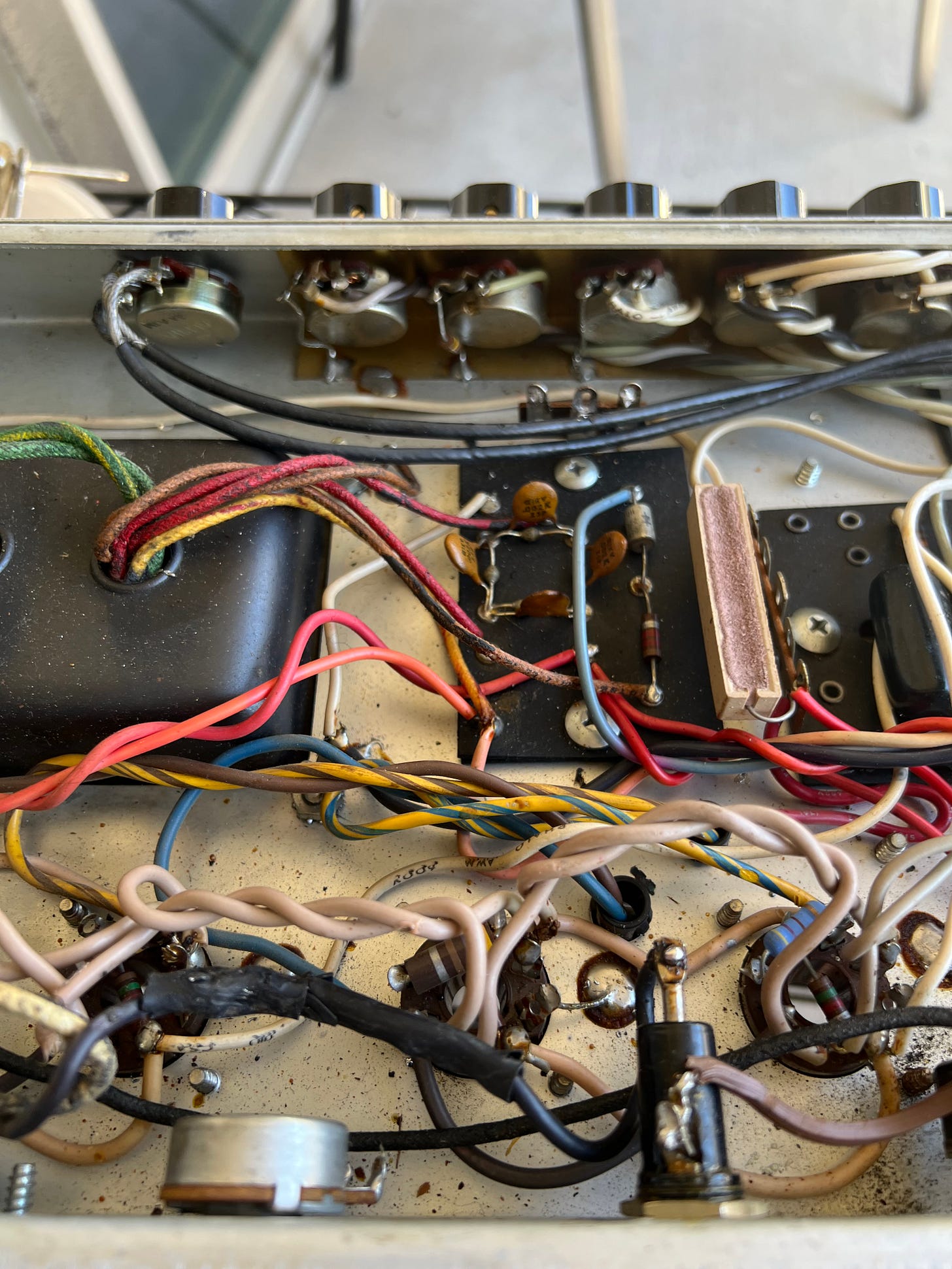

The most obvious departure point—one that will make my tech-writer partner chortle—involves how planning for these repair tasks required me to re-think reading and writing. Learning to read in and across different registers of knowledge and information induces responses keyed to learning styles that depart from the somewhat abstract thinking and imagining practices that are too often developed in literature classes. Developing a plan to work inside an actual amplifier, wired by specific people (in ways that vary even among the same model and year of amplifier) meant driving imagination more concretely towards action: to the point that just before doing one block of the repairs, I sat before my computer monitor displaying a “gutshot” of the wiring layout and practiced the moves I’d have to make with the soldering iron and pliers.

Besides practice, this writing and acting to learn enabled several levels of re-think as I gained familiarity both with what I’d be dealing with once my amp was open, and, more importantly, with how I’d be working. It was a simple thing: this practice made me see that I should switch the soldering iron from my right hand to my left. Immediately, much of my stress and fidgetiness with the danged thing diminished once I used the hand that I work best with for fine-motor stuff instead of trying to do what I’d seen other people do in the videos I watched.

These results confirm a frequently replicated research result: lasting learning results from an authentic and autonomously chosen learning goal (or goals). I wanted to maintain my amplifier. Learning how to do parts of this opened the possibilities of learning more about how they are designed, and what the components and circuits do.

This learning, subsequently, enabled me to reflect on how my goals and desires interacted with—or rather, were frustrated by—the claims and agendas held within much of the ‘vintage’ amp and guitar community. Which, fortunately for this upcoming digression, share a few communal shibboleths based on inaccurate, wrong, and/or magical thinking that you challenge at peril of ostracism. A repair guy posted a YouTube video introduction and guide to Fender “Ultralinear” amps, in which he repeatedly disclaimed replacing most of the consumable components unless they had already failed or were way out of spec. Because? That way we’d be hearing the amp the way it was originally designed. [See? textual originalism and editorial intent have migrated to all sorts of places.]

But, as with textual originalism, knowledge of actual contexts matters: do we care that the typesetters corrected the grammar and syntax for many ‘great’ writers? Do we care that the accounting departments nickeled & dimed engineers away from using components with less noise and tighter performance tolerances than what they would have preferred? So, there is an equally valid case to be made, both in terms of reliability and performance, to replace 40 year-old components with newer versions that will return the amp to original spec, and possibly realize the designer’s preferred sound.

Beyond that, the amps in question are not actually “ultralinear” and Fender did not market them as such: but someone started calling them that because they read the schematic wrong. [I love trying to learn to wrap my mind around this stuff, apparently many other people don’t.] The term stuck—mostly because the term helped cement their status as an undesirable product when people started to justify the high-price of “vintage” amps in terms of their “pleasing” non-linear distortion.

Sure, many many famous recordings were made using relatively tiny Fender Champs, Princetons, or Deluxes. But much of the recorded output of people like Hubert Sumlin and early rockabilly players prized for its tone was done with 50s Magnatone amps that were ultralinear. Or that a surprising number of records prized for their tone (like the first two Police albums or Pretenders’s stuff) . . . were also recorded with the very late 70s Fender Twins denigrated for their “sterility.” [As an aside, Never Mind the Bollocks by the Sex Pistols? done with a 1972 Twin. 2 of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s 3 guitarists also recorded with them (and actually performed with them—despite an endorsement deal with another manufacturer)].

In the process of planning for and performing this maintenance, I encountered the reality that catalyzed this piece about the inevitable differences of human-cnetered reading and writing: No two amplifiers in a production run of thousands, I’d bet, are actually wired identically.

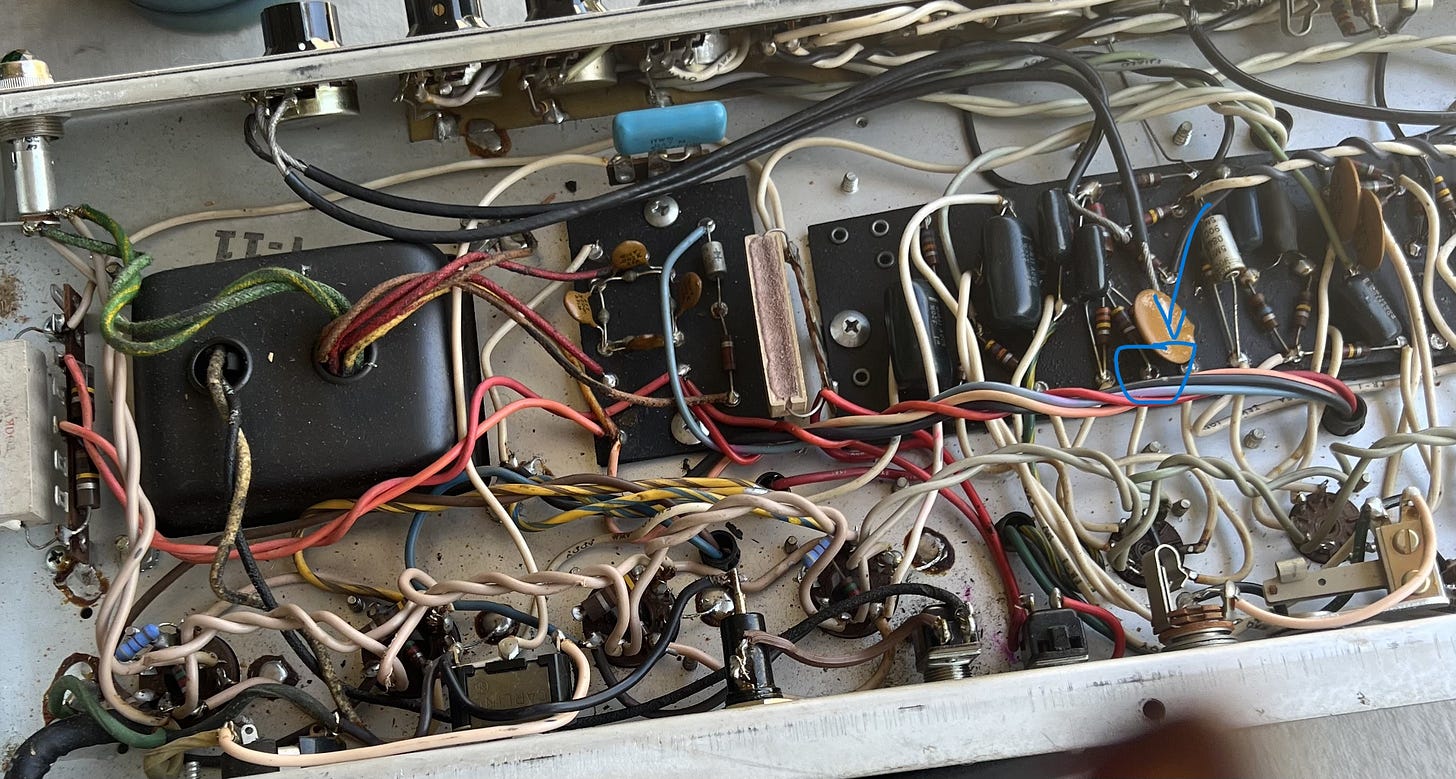

The blue lines enclose the a poorly-soldered joint that should not have passed Quality Control—yet it’s original (and perhaps explains a couple of this amp's peculiarities). Compared to other known original pieces, there are other differences apparent between this one and its fellow 1979 135 watt Fender Twins. (Which could make a decent case for using well-designed and produced automation practices, like circuit-boards and machine-soldering. Either that, or makes a decent case for training and respecting your workers who are actually responsible for realizing the design).

Seeing a transformation point from one example to another side of potentially analogous actions? If reading is a process of making something (a reading) out of component parts (various textual components and culturally-coded generic features, say), even starting with exactly the same components, no two readings will be the same. Partly from reader abilities, but also from possible variations in the components being assembled, or the conditions under which someone must work.

But a reading, or rather, a series of readings and experiences also can form circuits in our experiences. The conditions under which many people must learn to assemble readings, though, lead them detest reading. Or feel certain that they are incapable of it. Obviously, thinking about how my own experiences of reading and planning for amp repair differed from my accustomed habits of ‘literary’ reading prompted this waste of your time.

So much ‘reading,’ it would seem, is counter-revolutionary: designed to reinforce accustomed identities and assert a ‘timeless’ reality for recently manufactured norms (like, say, the traditional marriage, with goat-price optional). Or, the sympathies and emotions felt for fictional characters don’t get extended to people stuck in meat-space.

This where that turn to the rousing conclusion, or the application, or the “take-away” should happen. But won’t. Real problems rarely directly correspond to whatever we have read of experienced before. Even learning the design process, mastering the techniques, understanding the components and how they need to be laid out, there’s always the necessity for improvisation because something will happen unplanned. Always the chance that our ‘reading’ sends more energy to one character-path or event possibility, or bypasses another completely.

The long history of academic socialization in American education (and related processes in other cultures) ensure that some of these choices are forced. This is why we misread Hawthorne, for example, or why it isn’t common to see Melville as interested in the moments of missed opportunity and choice when history could have changed, but didn’t because (usually) some white dude couldn’t see reality right in front of him.

Is it possible that thinking of reading, thinking of texts, thinking of writing as exercises in assembling components into cognitive processing devices might enable more people to see reality in front of them—and, say, value Bartleby’s depression and spiritual questioning, or look for more examples of women’s communities formed and sustained through activism and material arts? Maybe. But the process wouldn’t fit into a 90 minute Continuing Education workshop.