amplification, or what if we're not hard-wired?

“Art,” insisted Ezra Pound, uses the “voltage of emotional energy.” “We might come to believe that the thing that matters in art is energy, something more or less electicity or radioactivity.” For Gi Taek Ryoo, this shows Pound incorporating Faraday’s electromagnetic theory into his concept of “Image” and his poetics. More generally, Pound’s move is one in a long series of using a ‘scientific’ phenomenon to drive a metaphor about what art does. Edgar Allan Poe can complain all he wants about science taking over from the fairies, but even he claimed psychotropic functions for poetics that stole from emerging pharmacology. Where’d this gambit start? Probably with arguing that texts were like textiles.

In the age of AI and printed circuit boards and micro-chips, it needs to stop—or, since I’m about to indulge in thinking it through, a little—it needs to be considered more thoroughly. The consequences harm us—especially in such widespread blather about being ‘hardwired’ or predisposed to ‘learning styles.’

Instead of being ‘hardwired’ and pre-formed, what if we use emerging information from child development to sketch out a model that sees kids as essentially existing in kit form: the pieces are there, but how they are assembled and formed requires intervention and interaction. A key question of our time: why do people not respond to signals the same way can be answered in an easy (& not incorrect) fashion: racism and misogyny. But what are the circuits and processes that makes these constructed responsed seem so real as to be inevitable?

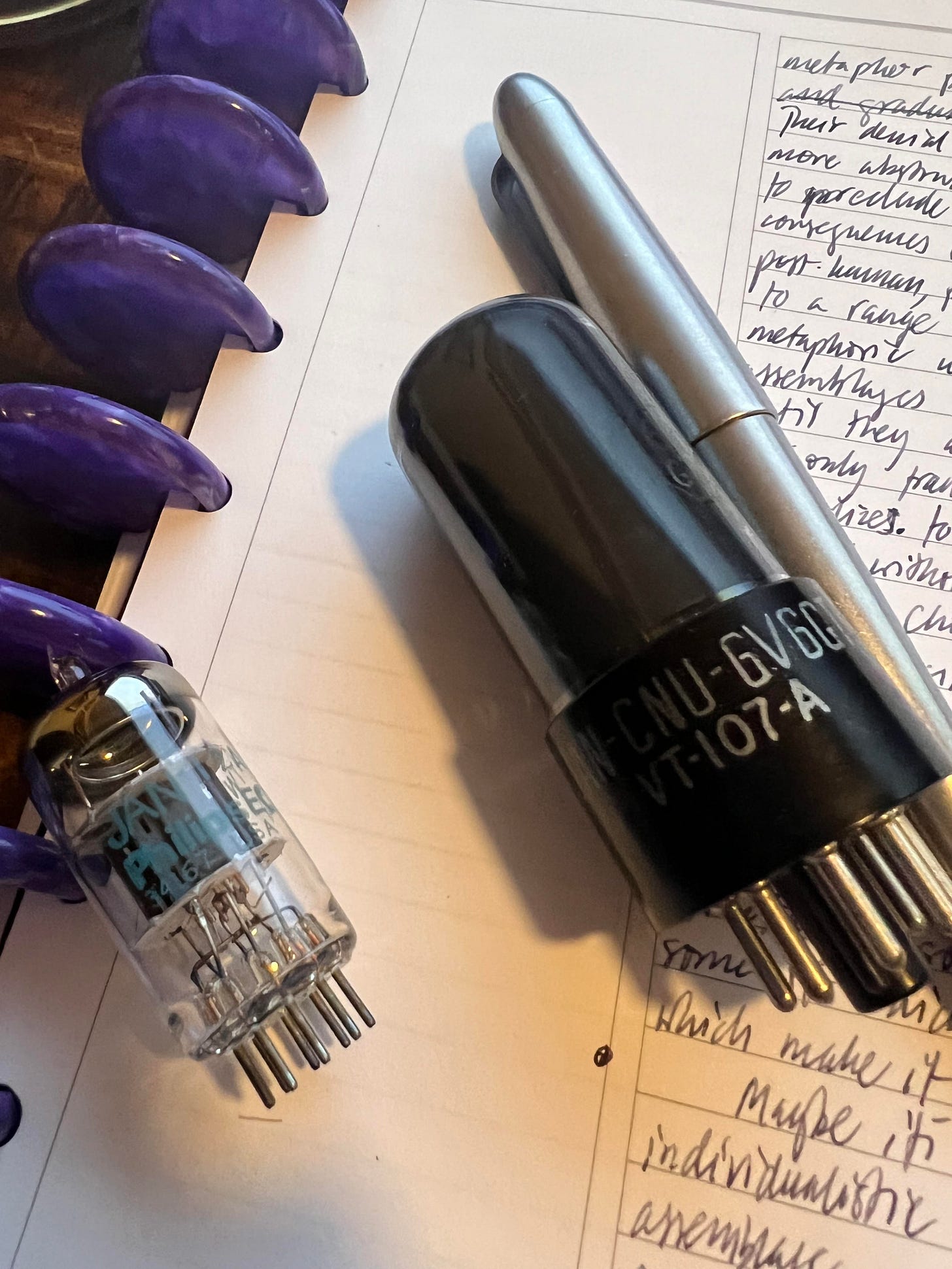

Even though the metaphor/analogy cannot help but be oversimplified, I’ve long pondered [insert Pinky and Brain pic] Pound’s dicta not in terms of grand theory, but in terms of amplifier design. Because, by it, art is, essentially, a circuit for processing voltage to make effects. Wander into thinking about instrument amplifiers, and you will soon be obsessing about voltage: “preamp and output tubes alike sound and perform differently when fed different voltage levels, so a rectifier that converts your power transformer’s 330V AC to 400V DC will result in your amp sounding a little different than it [would] with a rectifier that converts it to 350VDC.”

What? Don’t know what a rectifier is? We’ll sort of get there. Tubes? Aren’t they outdated—kind of—but that sentences above doesn’t work the same way with transistors in place, because there’s a good chance the transistor just shuts down instead of behaves differently—and that’s one reason why maybe analogizing our psychological processing to the most recent tech ‘innovation’ might be inappropriate.

For now, just know that the most important part of Angus Young’s stage rig is the Kikusui power conditioner that keeps his Marshall amps at a stable 236.1 volts whereever they are in the world. [USians—his amps don’t run on 120AC]. One of the levels of vintage amp enthusiasm involves the freak out about the differences in wall voltages between now and the 1950s and 1960s. [Bonus rabbit-hole: google Eddie Van Halen, Brown Sound, and Variac].

Analogy crossover point 1 (potentially): if emotions run off of ‘voltage,’ that voltage will require processing to identify and amplify a signal out of all of the composite potential signals. Smoothing, filtering, blocking, and shunting to ground all occur to isolate the desired signal. [If smoothing doesn’t happen, for instance, noise enters a circuit, and, in the case of a decision circuit, it could cause errors because of fluctuating voltage].

Capacitors—which, because people thought of them in terms of “electric fluid” for nearly a century, were referred to as “condensors” until the 1920s—perform many of these processes. They block direct current, can temporarily hold voltage, filter out various frequencies. It’s no wonder Freud was fascinated by them. In all sorts of devices the ‘power rail’ relies on seqeunced capacitors to provide the smooth direct current that makes everything from chips to tubes perform most happily.

The physics of how inter-related assemblies of capacitors, resistors, and tubes filter and amplify a tiny 1-2 volt signal to the 300+ volts that will drive an output transformer and speaker hits Fourier transform complexity: “any kind of signal can be looked [at] as a composition of single frequencies” (physics.stackexchange). How a circuit reproduces the multiple layers of overtones in a harmonic signal has long been a key figure in determining an amplifier’s desirability. People have long devalued my beloved late 1970s Fender Twins because of how dificult it is to get them to “break up.” I love mine, though, because its immense power reserves lets it reproduce a full guitar signal with depth and warmth even at ‘room’ volumes—it’s like listening to a hug.

So, pick your famous electric guitar sound. Assuming it was played by a human, and not copied and pasted in Logic or ProTools or Audacity, it started off as a more or less robust electro-magnetic voltage induced by some intervention of a person that made the strings vibrate in some way. Leaving aside the huge variables of pickup type and construction, wiring of components on the guitar, the capacitance of the cable,1 whatever effects processors might be involved, that intervention will deliver a 1-2 volt signal to the input stage of the amp.

Amplification can be as simple as one gain stage driving 1 power tube. It can involve 2 to 4 gain stages, various effects processes, phase inversion to split the signal and drive 2 (or 4) power tubes. The filtering can introduce 1 or more levels of frequency filtering. In a tube amp, all of this presumes effectively biased tubes. Even if this is not exactly the biasing you’re probably thinking about with respect to, say, racism and misogyny, perhaps there are analogies to be made between how setting up the voltage differentials in tubes affects their sensitivity and dynamic capacities and the differingt topographies of emotional sensitivity and response that comes to feel natural in human emotional experience.

“WARNING: A tube amplifier chassis contains lethal high voltage—sometimes over 700 volts AC and 500 volts DC.”

“Bias Voltage,” writes Rob Robinette, is the difference [in voltage] between a tube’s charged cathode and the tube’s control grid. This voltage differential controls how electrons from from the cathode to the plate. The signal enters the grid and usually will disrupt the bias point to encourage electron flow from the cathode across the grid to the plate—which drives that first amplification stage because it has 250 volts DC applied to it. Even with losses, a 1.5 volt AC signal will become much greater as it propagates. How much greater, and how nimbly it responds are matters for getting the power tube bias set right. A well-designed circuit allows for bias adjusting: tubes vary in their performance characteristics, components drift in value, and people just like how different settings sound.

Extrapolate this concept of biasing as a constructed and manipulable performance set point to people. Consider all of the interconnected components, devices, and sub-assemblies involved with amplifying and representing ‘voltage’ as emotional energy to us as people: a resistor out of value, a tube losing conductivity, a capacitor failing will all result in a differing (and decadent) filtering and amplification of voltage and introduction of noise and inharmonic distortion.

Is this very rough description of amplification analogous enough to what we could call a process of human emotional amplification to make it worth pursuing as an imaginary construct? It’s descriptive, not normative. It’s universal without being universalizing: there is no perfect amplifier circuit (although you will get people arguing that one). It provides a way of analyzing what happens once cognition selects and emphasizes (and de-emphasizes . . . i was astounded to learn how much signal is dumped to ground to produce a modern “high-gain” guitar sound) elements of experience to make the emotional valuations that drive our recognitions and qualitative attachments.

Those valuations, our recognitions and attachments are both real and fabricated. The “wiring” and and “biasing” happen, for most of us, in our early childhood as we learn how (or how not to) connect to those larger emotional circuits fashioned by families and social and institutional groupings. Even if most people seem convinced otherwise, it is modifiable, but at great risk and with way more difficulty than replacing a few capacitors in an amp.

Angus Young recorded Back in Black using a 1970s era wireless instead of a guitar cable because he liked the sound better. It remains basically his only ‘effect'.’